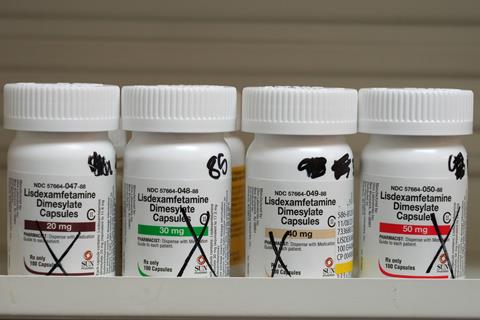

Drug shortages are a decades-old problem, but in recent years they have hit a record high. A steady stream of supply issues has disrupted supplies of life-saving medicines – from hormone replacement therapy (HRT), antibiotics and chemotherapy, to drugs used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as well as the latest diabetes and weight loss treatments.

Some of these shortages are now diminishing, as new supply lines come online or quality issues are resolved. But some are more persistent. Some of the drugs on the current US shortage list have been there for nearly a decade.

But what are the reasons behind this shortage and what is being done to ensure that patients have constant access to the medicines they need?

What is a drug shortage?

A drug shortage defines a period when the demand or estimated demand for a drug exceeds the supply. Drug shortages can occur for many reasons, including production and quality problems, delays, and discontinuations.

How big of a problem is drug shortages?

Medication shortages can compromise patient care by delaying treatment or diverting patients to other, inappropriate medications. They also put a strain on pharmacy teams trying to get the products they need and place an economic burden on the healthcare system by raising prices.

In the first quarter of 2024, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) – which actively monitors drug shortages in the US – along with the University of Utah’s Drug Information Service, tracked an “all-time high” of 323 active shortages, surpassing the previous record of 320 shortages in 2014 .

ASHP said most of the shortages involve low-cost generic drugs, especially sterile injectables used in hospital treatments and procedures, such as basic cancer treatment and intravenous antibiotics. Some of these drugs have no alternative, forcing hospitals and doctors to over-dose or even delay care.

The situation is no better in the UK. In November 2023, the British Generic Medicines Manufacturers Association (BGMA) reported that drug supply problems had reached record levels with a 100% increase in drug shortages between January 2022 and January 2024.

What’s more, the global nature of pharmaceutical supply chains means that shortages are often interconnected, meaning shortages in one country often affect others.

Why will there be drug shortages?

Reasons are multiple – geopolitical factors such as Brexit, the Ukraine-Russia war and the Covid-19 pandemic have had a significant impact on inventories, as well as rising energy costs and inflation, structural issues and the availability of raw materials.

One key reason for acute shortages is a sudden and unprecedented increase in demand, for example due to a rapid increase in the prevalence of disease. In December 2022, an increase in cases of Strep A among children in the UK caused increased demand for penicillin, amoxicillin and azithromycin, especially in solution, leading to nationwide shortages and a significant increase in wholesale prices.

New developments, such as the ‘Davina effect’ where an awareness campaign led by TV personality Davina McCall led to a sudden increase in demand for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in the UK, may put further pressure on supply chains. Since 2022, Novo Nordisk has struggled to ramp up production of Ozempic (semaglutide) to meet public demand. Originally developed as a diabetes treatment, demand for glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists increased after clinical trials showed the drug could be used off-label as a weight-loss agent and it was widely promoted by celebrities on social media.

Another reason for shortages is a sudden drop in supply. This could be due to recalls or quality issues – as when Indian manufacturer Intas, the main supplier of cisplatin and carboplatin cancer drugs to the US, failed a US Food and Drug Administration inspection last year, causing a nationwide shortage. Or because a company makes a business decision to stop producing an unprofitable product and there are not enough other suppliers. However, reduced supply can also be the result of natural disasters – for example, in 2023, a tornado hit a Pfizer plant in Rocky Mount, USA, destroying part of a large facility that produces a quarter of the company’s sterile syringes for US hospitals. .

Production problems, including shortages of raw materials or delivery methods, problems with industrial capacity and flexibility and distribution, or logistical problems, such as disruptions in international trade due to geopolitical conflict, can all contribute to shortages. Sterile injectables are particularly vulnerable to shortages compared to oral solids due to their expensive and more complex manufacturing processes.

The risk of drug shortages also increases due to the geographical concentration of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) production in China and India; two of the world’s largest pharmaceutical manufacturers. In 2018, research found traces of potentially carcinogenic nitrosamines in batches of the blood pressure drug valsartan originating from a factory in China, which was responsible for supplying APIs to many pharmaceutical manufacturers around the world. The result prompted several manufacturers to recall worldwide and raised concerns about continued drug supplies.

However, ASHP has said that the most serious and persistent shortages are driven by intense price competition among generic drug manufacturers, which undermines investment in manufacturing capacity, quality assurance and supply chain reliability, and leads to a lack of incentive to produce less profitable drugs. As a result, lower priced drugs are more likely to experience shortages.

What is the protocol when shortages occur?

Several countries have set up national reporting systems to make it easier to report shortages. For example, in the United States, manufacturers can notify FDA staff of drug shortages through a direct web portal, and the list is updated daily with new and resolved shortages, as well as additional information received from product suppliers regarding production capacity.

When a shortage occurs, the FDA works directly with the drug’s manufacturer to address the shortage and with other manufacturers to help increase production if they are willing to do so. If a shortage cannot be resolved immediately and the shortage involves an important drug needed by US patients, the FDA may look to a company willing and able to divert product into the US market to address the shortage.

In the UK, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) will contact drug manufacturers, other suppliers and wholesalers to secure additional supplies; the remuneration of clinical advice from the NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service and national clinical experts regarding management options and alternative medicines; and contact drugs that are important to identify potential sources of drugs.

In October 2019, the Serious Shortages Rules (SSPs) were introduced as part of preparations for a ‘no-deal’ Brexit to enable pharmacists to offer an alternative product specified in the protocol for products in short supply. Since then, DHSC has issued 61 SSPs, with the number of active protocols peaking at nine in July and September 2022.

The UK government has also restricted the export and storage of some medicines where there is evidence of, or risk of, serious shortages that could adversely affect UK patients. This list is reviewed and updated regularly.

And in 2020, DHSC established a national Disruption Response Service to address supply issues affecting medicines and other products.

Regulators, such as Lyfjastofnun, can also take a variety of regulatory actions, such as speeding up the evaluation process for new marketing authorizations; to provide temporary exemptions from drug labeling requirements so that drugs packaged for use in another country can be used; importation and testing of batches of licensed drugs; and consider manufacturers’ requests to import unlicensed drugs for the treatment of individual patients. Regulators in other countries have similar powers, but the details are different.

What is being done to limit shortages?

In December 2023, the European Medicines Agency published a list of more than 200 essential medicines to avoid potential shortages – it considers a medicine essential according to two main criteria: the severity of the disease it targets and the availability of other medicines. The list is planned to be expanded in 2024 and then updated every year.

At the end of April 2024, the EMA published recommendations to address weaknesses in the manufacturing and supply of medicines on the EU’s essential medicines list and to strengthen their supply chains.

As part of these recommendations, suppliers in Europe may be asked to take new measures such as stockpiling; review past shortages or back orders to help identify demand patterns; and increasing production capacity to avoid potential shortages of critical medicines in the supply chain.

There is currently limited transparency regarding the UK DHSC’s actions regarding decisions affecting supply chains and it is unclear whether the UK follows a similar system to the EU. In 2023, an organization representing UK pharmacists called for reforms to the systems used to manage shortages – for example to allow pharmacists to change prescriptions to provide alternatives for patients when medicines are out of stock. But in January 2024 the Government indicated it had no plans to bring forward such legislative proposals and would instead continue to rely on severe shortage rules to allow pharmacists to change prescriptions on a case-by-case basis.

In the United States, many policy solutions have been offered, including supplies and support for domestic and advanced manufacturing. The Biden administration has pushed to fund an increase in domestic manufacturing as a way to combat drug supply chain problems, with measures introduced in 2021 and this year to encourage more manufacturing capacity.

In April 2024, the US Department of Health and Human Services appointed a Supply Chain Resilience and Shortage Coordinator to lead in strengthening critical medical supply chains and related shortages.

And in May, the U.S. Senate Finance Committee drafted a bipartisan bill to ease the shortfall by having Medicare pay bonuses to hospitals and doctors for contracting practices that ensure adequate supplies of drugs — starting with generic sterile injectables and IVs, such as drug treatments.

#Explainer #drug #shortages #happen #reduce